Groundwater and Pathogens

This article summarises a review written for the UK Groundwater Forum by Brian Morris, formerly of the British Geological Survey. Follow this link to view the full review in PDF format.

Groundwater in the UK is generally of good quality, particularly with respect to pathogens (disease-causing organisms); typically very little treatment is required before it can be consumed. This makes groundwater an attractive source of drinking water and it is widely utilised by water companies and for private supplies. There are some situations however where contamination by pathogens could occur, with a risk to human health. These risks and the measures in place in the UK to manage them are the subject of this article.

Pathogens

Pathogens get into groundwater due to contamination by human or animal faeces or urine. Outbreaks of disease caused by these groundwater-borne micro-organisms are rare in the UK. This is because the subsurface environment is conducive to the self-purification of water. Nevertheless, the effects on health can be severe where infection occurs from waterborne diseases such as cholera, typhoid, infectious hepatitis, gastroenteritis, cryptosporidiosis and dysentery. With some of these diseases it only takes a very small dose to cause infection.

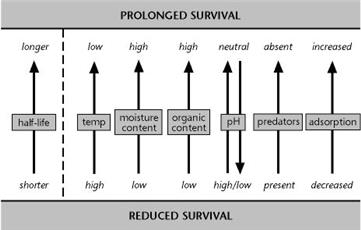

Factors affecting microbe survival and half-life (from Coombs et al 2000) ©NERC. All rights reserved

Soils have the capacity to reduce or eliminate pathogens that move into the ground with infiltrating water, for example through predation by naturally occurring soil fauna. However, in some situations pathogens by-pass the soil zone - septic tanks, latrines, soakaways, old farm waste stores and leaking sewers are prime examples. The unsaturated zone of the rock beneath the soil can also make it difficult for pathogens to migrate to the water table and, being typically an aerobic environment, bacterially-mediated degradation can be both rapid and effective. Where the unsaturated zone is thick and the movement of water slow, the time taken to reach the water table is usually long enough for most pathogens to die off.

Once below the water table the speed with which pathogens move will mostly depend on how fast the groundwater moves. Standards widely used in the UK and elsewhere for protecting groundwater supplies are based on the observation that most pathogens will have died off within 50 days of entering the ground. There is still a risk though with rocks that have fast flowpaths, such that the travel time from the ground surface to a spring or well is relatively short, for example karstic limestone.

The risk of pathogen contamination of water supplies can also be increased by poor well design, construction and maintenance. For example, where the seal around the headworks of a borehole is not in tact, polluted water can rapidly enter the water supply from the surface.

Protecting water supplies

Additional protection measures may be imposed by the owner of a groundwater supply or by the environment regulator to further reduce contamination risk. In England and Wales the Environment Agency has devised source protection zones (SPZs) for all groundwater supplies intended for human consumption. While larger abstractions such as public water supplies and breweries have bespoke SPZs, smaller private supplies have a default 50 metre radius inner zone which serves as a sanitary control area and an outer zone within which highly contaminating activities should be controlled. The bespoke zones are based on estimated travel time of groundwater to the pumping station. SPZ 1 corresponds to a 50-day travel time, while SPZ 2 corresponds to a 400-day travel time. More information about SPZs can be found in the Environment Agency’s Groundwater Protection: Policy and Practice: Part 4 legislation and policies

Private water supplies are also protected by legislation. The Private Water Supply Regulations 2009 (England) and the Water Supply Regulations 2006 (Scotland) require local authorities to keep a register of all private water supplies and to undertake regular monitoring to identify any risk to human health. The regulations in England also require local authorities to complete a risk assessment for each private supply every 5 years, to determine how detailed the monitoring needs to be. Local arrangements for private water supply registration and monitoring in your area can be obtained from the Environmental Health Department of your Local Authority - see our FAQ on private boreholes.

Public groundwater supplies are rarely the cause of waterborne disease outbreaks because the sources are well-maintained, activities in their vicinity are well controlled by the SPZs, water quality is monitored and precautionary disinfection is widely practised. Private groundwater supplies are more prone to water quality problems as they often tap shallower groundwater systems (through wells or springs), are less well-regulated and are not treated routinely. In England and Wales in 1996, a survey of 91 private supplies across 10 local authorities found nearly half failed to meet national microbiological water quality standards

Special Concerns over Cryptosporidium

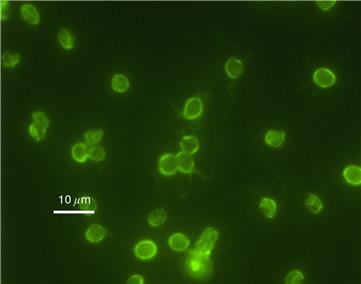

Oocysts of the parasite Cryptosporidium (which causes cryptosporidiosis outbreaks) are found widely in the environment and can survive for long periods outside their hosts. A large outbreak in North London in 1997 with 345 confirmed cases was traced to a public groundwater supply.

Cryptosporidium oocysts - source http://de.academic.ru/dic.nsf/dewiki/286758

After the 1997 outbreak it was realised that the resistance of Cryptosporidium to standard (precautionary) disinfection treatment made it a real hazard to groundwater-based public supplies, which provide water for 20 million people in England and Wales.

New water regulations were therefore introduced in 1999 requiring a treatment standard of an average of <1 oocyst per 10 litres of water for public water supplies and the completion of a risk assessment. The risk assessments found one fifth of treatment works in England and Wales were at significant risk of Cryptosporidium contamination, about half of which were plants treating groundwater. Water companies were required by the Drinking Water Inspectorate (DWI) to either: shut down the supply; install new treatment facilities; or implement continuous monitoring.

As a result, more than one quarter of supplies were shut down, a similar number introduced better treatment while the remaining supplies continued in operation with rigorous monitoring. A 2007 review of this screening and monitoring process concluded that it had been a successful preventive health measure.

Links

England and Wales

Drinking Water Inspectorate

Drinking Water Inspectorate – Private water supply information leaflet

Scotland

Drinking Water Quality Regulator for Scotland

Scottish Government's Private Water Supplies web site

Northern Ireland

Drinking Water Inspectorate – NIEA

Print this Page